What is Docker?

- The Tech Platform

- Sep 26, 2020

- 6 min read

The word "Docker" refers to several things, including an open source community project; tools from the open source project; Docker Inc., the company that primarily supports that project; and the tools that company formally supports. The fact that the technologies and the company share the same name can be confusing.

Here's a brief explainer:

The IT software "Docker” is containerization technology that enables the creation and use of Linux® containers.

The open source Docker community works to improve these technologies to benefit all users.

The company, Docker Inc., builds on the work of the Docker community, makes it more secure, and shares those advancements back to the greater community. It then supports the improved and hardened technologies for enterprise customers.

With Docker, you can treat containers like extremely lightweight, modular virtual machines. And you get flexibility with those containers—you can create, deploy, copy, and move them from environment to environment, which helps optimize your apps for the cloud.

How does Docker work?

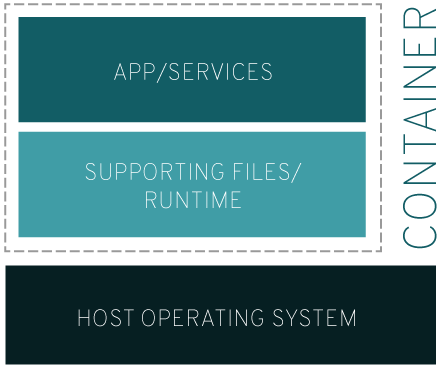

The Docker technology uses the Linux kernel and features of the kernel, like C groups and namespaces, to segregate processes so they can run independently. This independence is the intention of containers—the ability to run multiple processes and apps separately from one another to make better use of your infrastructure while retaining the security you would have with separate systems.

Container tools, including Docker, provide an image-based deployment model. This makes it easy to share an application, or set of services, with all of their dependencies across multiple environments. Docker also automates deploying the application (or combined sets of processes that make up an app) inside this container environment.

These tools built on top of Linux containers—what makes Docker user-friendly and unique—gives users unprecedented access to apps, the ability to rapidly deploy, and control over versions and version distribution.

What's a Linux container?

A Linux® container is a set of 1 or more processes that are isolated from the rest of the system. All the files necessary to run them are provided from a distinct image, meaning Linux containers are portable and consistent as they move from development, to testing, and finally to production. This makes them much quicker to use than development pipelines that rely on replicating traditional testing environments. Because of their popularity and ease of use containers are also an important part of IT security.

Why use Linux containers?

Imagine you’re developing an application. You do your work on a laptop and your environment has a specific configuration. Other developers may have slightly different configurations. The application you’re developing relies on that configuration and is dependent on specific libraries, dependencies, and files.

Meanwhile, your business has development and production environments that are standardized with their own configurations and their own sets of supporting files. You want to emulate those environments as much as possible locally, but without all the overhead of recreating the server environments. So, how do you make your app work across these environments, pass quality assurance, and get your app deployed without massive headaches, rewriting, and break-fixing? The answer: containers.

The container that holds your application has the necessary libraries, dependencies, and files so you can move it through production without nasty side effects. In fact, the contents of a container image can be thought of as an installation of a Linux distribution because it comes complete with RPM packages, configuration files, etc. But, container image distribution is a lot easier than installing new copies of operating systems. Crisis averted–everyone’s happy.

That’s a common example, but Linux containers can be applied to many different problems where portability, configurability, and isolation is needed. The point of Linux containers is to develop faster and meet business needs as they arise. In some cases, such as real-time data streaming with Apache Kafka, containers are essential because they're the only way to provide the scalability an application needs. No matter the infrastructure—on-premise, in the cloud, or a hybrid of the two—containers meet the demand. Of course, choosing the right container platform is just as important as the containers themselves.

Red Hat® OpenShift® includes everything needed for hybrid cloud, enterprise container, and Kubernetes development and deployments.

Docker vs. Linux containers: Is there a difference?

Although sometimes confused, Docker is not the same as a traditional Linux container. Docker technology was initially built on top of the LXC technology—which most people associate with "traditional” Linux containers—though it’s since moved away from that dependency. LXC was useful as lightweight virtualization, but it didn’t have a great developer or user experience. The Docker technology brings more than the ability to run containers—it also eases the process of creating and building containers, shipping images, and versioning of images, among other things.

Traditional Linux containers use an init system that can manage multiple processes. This means entire applications can run as one. The Docker technology encourages applications to be broken down into their separate processes and provides the tools to do that. This granular approach has its advantages.

Advantages of Docker containers

Modularity

The Docker approach to containerization focuses on the ability to take down a part of an application to update or repair, without having to take down the whole app. In addition to this microservices-based approach, you can share processes among multiple apps in much the same way service-oriented architecture (SOA) does.

Layers and image version control

Each Docker image file is made up of a series of layers that are combined into a single image. A layer is created when the image changes. Every time a user specifies a command, such as run or copy, a new layer gets created.

Docker reuses these layers to build new containers, which accelerates the building process. Intermediate changes are shared among images, further improving speed, size, and efficiency. Also inherent to layering is version control: Every time there’s a new change, you essentially have a built-in changelog, providing you with full control over your container images.

Rollback

Perhaps the best part about layering is the ability to roll back. Every image has layers. Don’t like the current iteration of an image? Roll it back to the previous version. This supports an agile development approach and helps make continuous integration and deployment (CI/CD) a reality from a tools perspective.

Rapid deployment

Getting new hardware up, running, provisioned, and available used to take days, and the level of effort and overhead was burdensome. Docker-based containers can reduce deployment to seconds. By creating a container for each process, you can quickly share those processes with new apps. And, since an operating system doesn’t need to boot to add or move a container, deployment times are substantially shorter. Paired with shorter deployment times, you can easily and cost-effectively create and destroy data created by your containers without concern.

So, Docker technology is a more granular, controllable, microservices-based approach that places greater value on efficiency.

Are there limitations to using Docker?

Docker, by itself, can manage single containers. When you start using more and more containers and containerized apps, broken down into hundreds of pieces, management and orchestration can get difficult. Eventually, you need to take a step back and group containers to deliver services—networking, security, telemetry, and more—across all of your containers. That's where Kubernetes comes in.

With Docker, you don’t get the same UNIX-like functionality that you get with traditional Linux containers. This includes being able to use processes like cron or syslog within the container, alongside your app. There are also limitations on things like cleaning up grandchild processes after you terminate child processes—something traditional Linux containers inherently handle. These concerns can be mitigated by modifying the configuration file and setting up these abilities from the start–but that may not be obvious at a first glance.

On top of this, there are other Linux subsystems and devices that aren’t name spaced. These include SELinux, C groups, and /dev/sd* devices. This means that if an attacker gains control over these subsystems, the host is compromised. In order to stay lightweight, the sharing of the host kernel with containers opens this possibility of a security vulnerability. This differs from virtual machines, which are much more tightly segregated from the host system.

The Docker daemon can also be a security concern. To use and run Docker containers, you’ll most likely be using the Docker daemon, a persistent runtime for containers. Docker daemon requires root privileges, so special care must be taken regarding who gets access to this process and where the process resides. For example, a local daemon has a smaller attack surface than one that lives in a more public location, such as a web server.

Comments